November 11, 1918 was no happy day for Germany. The Armistice had been signed on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month and the “war to end all wars” was over — Germany had lost. As jubilation poured out on the streets of Europe and America, revolution poured through German streets as Kaiser Wilhelm II fled to exile in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, Ludovica Koch and Gustav Ludwig Schmidt were preparing for the birth of their son Helmut Schmidt, who would arrive the following month.

Young Schmidt, like many Germans of that era, hated the terms of the German surrender and expressed that dissatisfaction by becoming a leader of the Hitler Youth, though it did not last long — he quickly soured to the Nazi ideology, fighting for his country in WWII as a reluctant supporter of what he viewed as a lesser evil. After the war, he completed his degree in Hamburg and quickly entered the political fray, becoming an active member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

He worked his way through party ranks for three decades, finally becoming Chancellor of West Germany in 1974. Meanwhile, the Red Army Faction, a far-left West German militant group, was becoming bolder in its attempt to influence social change and was classified a terrorist organization by the German government. Many of its leaders were jailed.

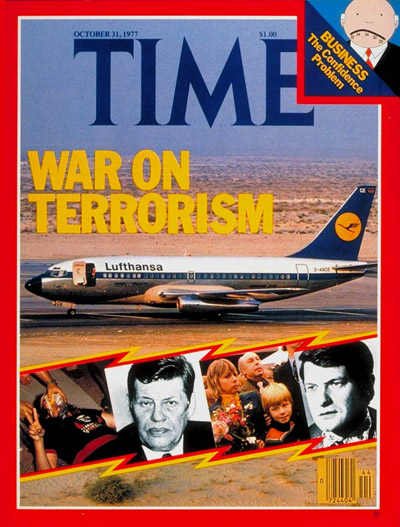

In solidarity with its Marxist brethren, a group called the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, who had successfully hijacked several planes over the preceding years and were a direct cause for the introduction of security screening at airports, decided to take action. On October 13, 1977, the group hijacked Lufthansa flight LH181, a Boeing 737-200 flying from Palma de Mallorca to Frankfurt, as a bargaining chip to secure the release of Red Army Faction Leaders.

The plan was to fly the hijacked plane directly to Larnaca, Cyprus, but there was insufficient fuel and the plane was diverted to Rome for refueling. Germany demanded that the Italian government shoot the tires of the aircraft so it could not take off, but the Italians refused, not wanting to further subject their own aircraft to hijacking, and let the plane take off.

The plane made it to Larnaca where negotiations to release the 91 hostages broke down. The plane refueled and took off again for Beirut. Approaching Beirut, clearance for landing was denied. The plane continued on but was also denied landing permission in Damascus, Baghdad, and Kuwait City. With fuel low, the airliner made an emergency landing in Bahrain.

On the ground, the plane was immediately surrounded by armed soldiers but the terrorist group claimed it would kill the first officer if the troops did not back off. They did back off. The aircraft was refueled and took off for Dubai.

Dubai also did not want to deal with the hijackers and denied landing permission, even setting up obstacles on the runway to prevent a landing. The hijackers said they were coming in anyway and as they rapidly descended toward the airport, the obstructions (mostly fire engines and trucks) were removed. In Dubai, the hijackers demanded more fuel, food, medicine, newspapers, and even to have the trash removed onboard.

Back in Germany, Chancellor Schmidt was furious. This was an era of hijackings and the chain-smoking leader was sick and tried of fostering more hijackings by giving in to hijacker demands. He sent a team of elite GSG 9 members (German special ops) to Dubai to try to free the hostages but faced political pushback from Sheikh Mohammed, now the Emir of Dubai but then a UAE Defense Minister. Finally, permission was granted but the Germans wanted to practice first — staging dry-runs on an adjacent airstrip for nearly two days. It was too late…just after midnight on October 17th, the refueled aircraft took off again.

Back in Germany, Chancellor Schmidt was furious. This was an era of hijackings and the chain-smoking leader was sick and tried of fostering more hijackings by giving in to hijacker demands. He sent a team of elite GSG 9 members (German special ops) to Dubai to try to free the hostages but faced political pushback from Sheikh Mohammed, now the Emir of Dubai but then a UAE Defense Minister. Finally, permission was granted but the Germans wanted to practice first — staging dry-runs on an adjacent airstrip for nearly two days. It was too late…just after midnight on October 17th, the refueled aircraft took off again.

The hijackers attempted to land in Oman but were denied and went on to Yemen, where landing permission was also denied. Out of fuel again, another emergency landing was declared but this time the obstructions were not removed from the two runways in Aden. The aircraft landed in sand on a strip parallel to the runways.

Captain Jürgen Schumann was given permission to exit the aircraft to inspect for possible damage but disappeared, allegedly to plea with the Yemeni authorities not to let the aircraft off the ground. Angry at his long absence, the hijackers immediately shot him in the head in front of the passengers upon his return to the aircraft.

Refueled once again, the plane took off for Somalia and landed in Mogadishu. Captain Schumann’s body was thrown on the tarmac and an ultimatum was made that if the Red Army Faction prisoners were not released in the next nine hours, the plane would be blown up with all passengers onboard.

Time ticked and there was no word from the German government. The hijackers began dousing passengers in alcohol so they would incinerate quickly when the plane was blown up. With only minutes before the deadline, the hijackers were told that the West German government would release the hostages but needed more time. They were given an eight hour extension.

Meanwhile back in Germany, Chancellor Schmidt dispatched a GSG 9 team from Bonn to Djibouti to prepare for a rescue attempt. Another team had arrived earlier from Jeddah. The Boeing 707 landed with lights out to avoid arousing the suspicion of the hijackers. Immediately, the team went to work, using black-painted ladders to stealthily access the aircraft via escape hatches on the fuselage.

As a diversionary tactic, Somali soldiers lit a fire several hundred feet in front of the jet. Two of the three hijackers rushed into the cockpit to see what was going on (the fourth hijacker had jumped off the plane upon landing in Mogadishu many hours earlier). Simultaneously pulling open the exit doors, German commandos stormed aboard, ordering passengers in German to hit the floor and quickly took out two of the three hijackers, wounding the third who would die hours later. With the exception of Captain Schumann, all hostages survived.

Chancellor Schmidt’s gamble had worked. The young boy who had grown up in the shadow of Germany’s WWI humiliation was no longer humiliated — he had decisively acted and earned great respect for his leadership. Germany would never negotiate with airline hijackers again.

(with thanks to Wikipedia for helping me better understand the incident — photo credit goes to Wikimedia commons)

Nette Geschichte 🙂

I second your Frau’s comments – a good read. Glad to know that this ended differently than many hijackings tended to. As a teenager in the 80’s I remember reading about the activities carried out by the Red Army Faction (primarily assassinations of business execs and bombings at military bases). It emboldened me to join the Army and I ultimately was stationed in Germany in the Frankfurt area. Fortunately by the time I completed my tour of duty in 1990 they were no longer very active.

Thanks for this post, Matthew. A very enjoyable read.