I’ll be the first to admit that I really don’t see what the big deal is about the solar eclipse today. I will not be leaving Los Angeles and will not even step outside during the eclipse if I’m in the middle of something. But a ride on the Concorde? That’s another story…

The Concorde was in its final stages of testing in 1973..the same year as a historic solar eclipse.

As French and British aviation engineers readied their Concordes for passenger flight, the solar astronomy world was gearing up for its own milestone: the longest total solar eclipse of a lifetime, on June 30, 1973. The eclipse promised a luxurious view if you stood at the right place on the planet: a maximum of 7 minutes and 4 seconds as the moon passed over the Sahara Desert. It would be just 28 seconds short of the longest possible eclipse viewable from Earth; in the preceding several hundred years, there had only been one eclipse longer than this one, and there would not be a longer total solar eclipse until June 2150.

A group of astronomers hatched a bright idea…why not use Concorde to stretch out the eclipse? Theoretically, they could increase the viewpoint period tenfold, from seven minutes to 70 minutes. Furthermore, since the Concorde flew “above the weather” it would eliminate most obstructions.

But it was not like they could just waltz into Aérospatiale/BAC and demand a charter. The plane had never even flown commercial yet.

Britain or France?

The scientists first approached the British, but were rebuffed. Concurrently, a group of French scientists approached Concorde’s French division with the following proposal:

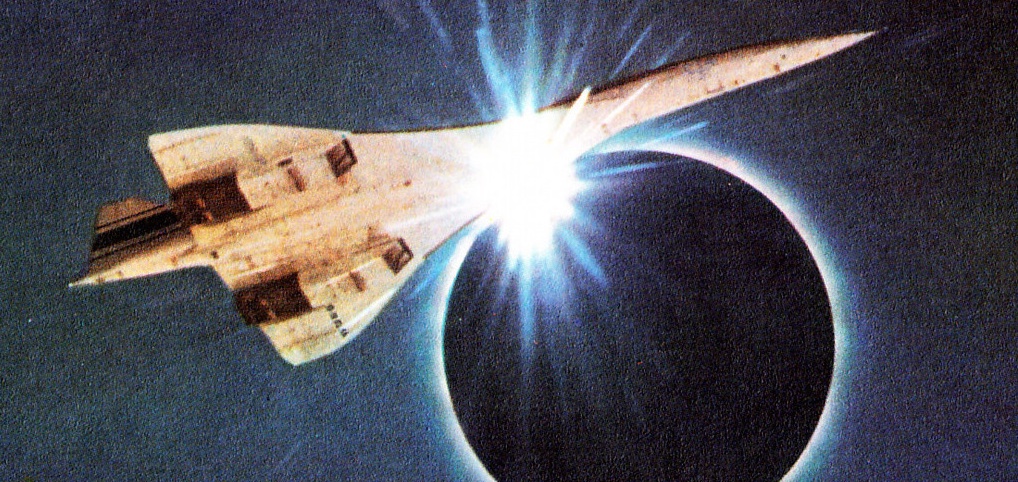

The plan seemed deceptively simple. Closing in at maximum velocity, Concorde would swoop down from the north and intercept the shadow of the moon over northwest Africa. Traveling together at almost the same speed, Concorde would essentially race the solar eclipse across the surface of the planet, giving astronomers an unprecedented opportunity to study the various phenomena made possible by an eclipse: the ethereal solar corona, the effect of sunlight on the darkened atmosphere, and the brief red flash of the chromosphere, a narrow region around the sun that’s usually washed out by the much brighter photosphere.

Aérospatiale liked the plan and agreed to fund it.

As the eclipse approached, final preparations were made–

Nothing could short-circuit—an onboard fire would be catastrophic—and everything had to be built to withstand the vibrations on takeoff: an afterburner-driven sprint that would accelerate Concorde to 250 miles-per-hour even before lift-off, pinning passengers firmly back against their seats. And, despite the aircraft’s clean safety record at that point, in the back of the scientists’ minds were legitimate concerns about flying in any experimental aircraft at supersonic speeds.

The day finally arrived and the aircraft, filled with five teams of scientists, rocked down the runway in Gran Canaria, Spain. A reminder of one reason the Concorde is grounded–

Just taxiing for take-off, the Concorde burned more fuel than a 737 flying from London to Amsterdam, a fact which contributed to its eventual grounding.)

You can read far more details of this fascinating story here, but the mission was a smashing success.

Here’s a short documentary video on the Concorde mission:

CONCLUSION

Will the Concorde ever fly again? Maybe. A group of aviation enthusiasts in England is trying to acquire one aircraft and make it airworthy. In the meantime, Lockheed and NASA are working on a 21st century supersonic transport. Who knows, may be in our lifetime we’ll have the chance to chase a solar eclipse via an aircraft traveling at twice the speed of sound. That’s something I’d get excited about.

H/T: Fake Oscar Munoz // image courtesy of http://flight-time.tumblr.com

Now this is a suitable eclipse story for boardingarea…. keep it up!!