The U.S. DOT has issued its verdict on United Airlines’ unilateral decision to cancel thousands of cheap first class tickets, ruling that it will not take action against United for failing to honor the fare. Although this ruling comes as no surprise, the DOT’s twisted legal analysis merits clarifying legal analysis.

The U.S. DOT has issued its verdict on United Airlines’ unilateral decision to cancel thousands of cheap first class tickets, ruling that it will not take action against United for failing to honor the fare. Although this ruling comes as no surprise, the DOT’s twisted legal analysis merits clarifying legal analysis.

My Prediction Was Spot On

Last week, I speculated on the rationale DOT would use to justify United’s rescission of these fares in contravention of the unambiguous regulations of 49 U.S.C. 41712 §399.88(a).

I imagined a ruling stressing that consumers had to manipulate united.com in order to book this fare (by navigating to the Danish UA website) while perhaps leaving an opening for recourse for those with bonafide Danish billing addresses.

Indeed, that was the primary rationale used by the DOT in siding with United, yet the DOT went further than I imagined.

Line-By-Line Analysis of DOT Ruling

Let’s break down the entire DOT letter. You can read it here in its entirety first if you prefer.

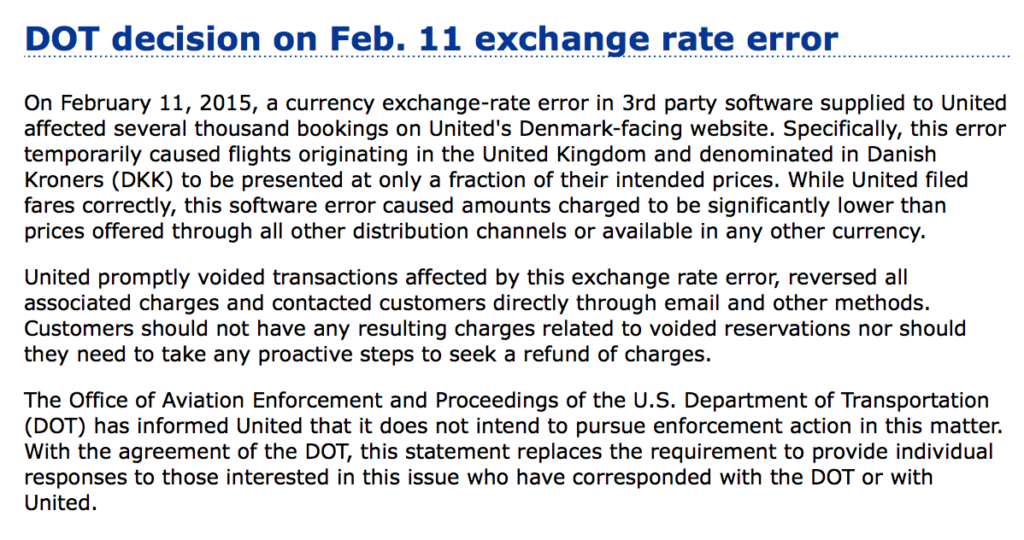

The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of Aviation Enforcement and Proceedings (Enforcement Office) has completed its review of the mistaken fares that appeared on United Airlines’ (United) Denmark website on February 11, 2015. During the past two weeks, thousands of consumers who purchased tickets from United’s Denmark website at the mistaken fare levels have contacted the Enforcement Office asking that United be required to honor those fares based on the Department’s rule against post-purchase price increases of scheduled air transportation.

The intro paragraph sheds light on two matters. First, DOT immediately sides with United in the description of these fares as “mistaken”, using that adjective twice rather than a more neutral word. The controversy is not whether United intended to offer $50 transatlantic first class fares, but whether they could tautologically be deemed mistaken when united.com indicated a clearly published price in exchange for flights and charged credit cards in that amount.

Second, DOT notes that it received “thousands” of consumer complaints — proof not only that many took advantage of this mistake fare (United had said “several thousand” bookings were made), but that the DOT’s prohibition against post-purchase price increases ensconced in 49 U.S.C. 41712 §399.88(a) has permeated beyond the confines of the blogosphere and Flyertalk to become an intrinsic consumer reaction to dealing with unilaterally cancelled airfare.

After a careful review of the matter, including the thousands of submissions from consumers and information from United, the Enforcement Office has decided that it will not take action against United for not honoring the tickets.

Do numbers matter? Why mention “thousands of submissions” again? I would think that if hundreds of thousands had booked instead of thousands, the DOT would have been even more likely to side with United, adding undue financial harm to its rationale for backing United. It is even conceivable the DOT is playing a bit of a word game, implicitly stating that one reason it chose not to enforce the fares was because too many complained about it.

The mistaken fares appeared on a website that was not marketed to consumers in the United States.

In order to purchase a ticket, individuals had to go to United’s Denmark website which had fares listed in Danish Krone throughout the purchasing process.

Not exactly. The fare did only appear on United’s Danish website, but it does not follow that it appeared on a website that is not marketed to U.S. consumers. First, it all happened on united.com. Second, switching billing countries could be viewed as a means to coax united.com into functioning properly rather than a means to defraud the company. Third, and most importantly, the very inclusion of this sentence marks a departure from past DOT interpretation stating the prohibition against post-purchase price increases applies to all airfare that touches the United States. (cf. RGN fare mistake). Never before has a “marketing” distinction been made.

In addition, only people who identified “Denmark” as their location/country where billing statements are received when entering billing information at the completion of the purchase process were able to complete their purchase at the mistaken fare levels.

Certainly this might be a reason for United to pursue fraud claims, but I fail to understand what this sentence has to do with §399.88(a), which makes no distinction about billing address.

Consistent with the Office’s treatment of fare advertisements and disclosure of baggage fees, it does not intend to enforce the rule in question (the post-purchase price increase prohibition) when the fare offer is not marketed to consumers in the United States.

This is just sloppy and incoherent reasoning. First off, it is a derogation of the DOT’s duty to protect consumers from predatory airline practices. But more practically, it is factually inaccurate to assume that consumers in the United States and Denmark are mutually exclusive. The DOT leaves open a door for Danish consumers to still seek redress against United, but defies logic in insinuating that the fare is not marketed to consumers in the U.S. just because the currency was not shown in USD.

Additionally, the Office is concerned that to obtain the fare, some purchasers had to manipulate the search process on the website in order to force the conversion error to Danish Krone by misrepresenting their billing address country as Denmark when, in fact, Denmark was not their billing address country. This evidence of bad faith by the large majority of purchasers contributed to the Enforcement Office’s decision.

And there it is — a brand new rationale for chipping away at §399.88(a). The law makes no distinction for good or bad faith purchases for good reason — bad faith is not always so clear cut. Arguably, the deliberate input of a false billing address is clear evidence of bad faith, but DOT should not be in the business of making this determination when the regulations make no allowance for bad faith exceptions–

§ 399.88 Prohibition on post-purchase price increase. (a) It is an unfair and deceptive practice within the meaning of 49 U.S.C. 41712 for any seller of scheduled air transportation within, to or from the United States, or of a tour (i.e., a combination of air transportation and ground or cruise accommodations), or tour component (e.g., a hotel stay) that includes scheduled air transportation within, to or from the United States, to increase the price of that air transportation, tour or tour component to a consumer, including but not limited to an increase in the price of the seat, an increase in the price for the carriage of passenger baggage, or an increase in an applicable fuel surcharge, after the air transportation has been purchased by the consumer, except in the case of an increase in a government-imposed tax or fee. A purchase is deemed to have occurred when the full amount agreed upon has been paid by the consumer.

What does “the full amount agreed upon” mean? It seems to me the only reasonable answer is not to argue that “United would not have offered that had it known…” but to use the logic of the classic Lucy v. Zehmer case, namely that if a price is offered for an item, even if it is only $50, and “hands are shaken” in the form of a reservation being created, credit card charged, and ticket issued, then there is a binding contract, even if United realizes later that it acted sloppily or never subjectively intended to sell at that price. United is not a person, but a corporation operating, in part, through its website. The website is United and objectively, the website is United’s “mouthpiece” for signing contracts. United offered a fare at a clearly published price throughout the booking process, accepted payment for it, and issued the ticket. Sorry United…you made a deal.

United immediately blamed the problem on a third party provider — likely ITA Software or ATPCO — and it still seems to me that United’s recourse is with that third party and not the consumer who simply took advantage of an offer united.com offered, as ludicrous as the offer appeared.

To ensure that the Office’s determination that United is not required to honor the mistaken fare is available to all affected consumers expeditiously, the Office is placing this notice on its website rather than responding separately to each individual who has contacted the Department.

Rather than send out an e-mail response to each customer, the DOT has chosen to simply post its ruling on its website. That’s fine, but this is quite curious–

The Office has also agreed that United may choose to post information about its handling of this incident in a prominent location on its website instead of providing individual responses to consumers who submitted an inquiry to United or the Department regarding this matter. We believe that posting of information by the Department and United is the best course of action as it offers the most effective means of reaching as many consumers as possible at the same time.

Wait just a minute. United canceled these tickets without providing notice to affected travelers and now does not even owe an explanation to those who wrote in questioning United’s action. Note that DOT says it has “agreed” that United may post its decision on its website in lieu of individual e-mails. This evidences that United and the DOT have been working closely the entire time. Does it bother you that United and DOT had a seat at the negotiation table but consumers did not, at least beyond their complaint e-mails? How can a small post on united.com (see below) be “more effective” than contacting each customer implicated by this cancellation? It just makes no sense — the DOT ruling seems like a press release from United rather than a carefully reasoned decision from a consumer advocate agency that had promised that not even mistake fares were exempt from its prohibition against post-purchase price increases.

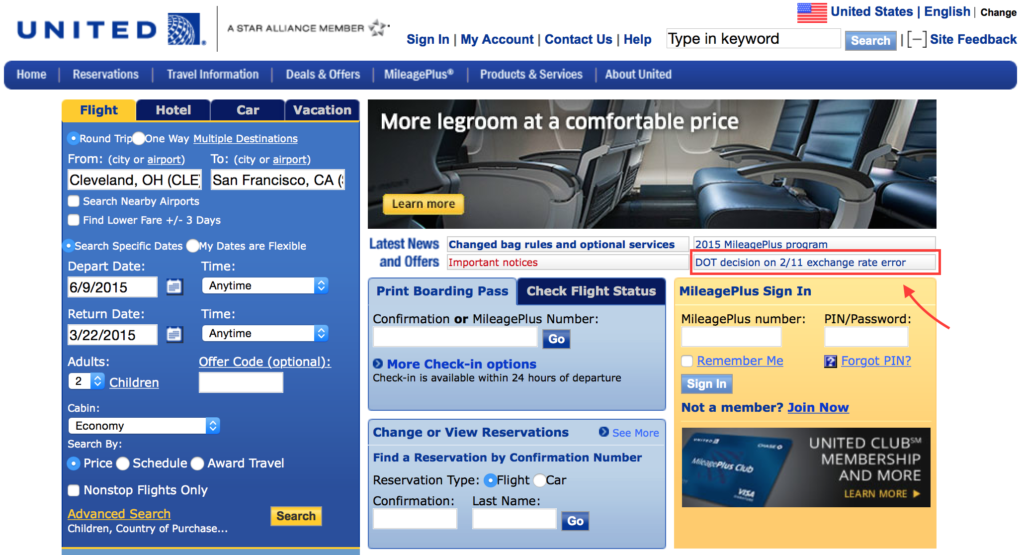

That’s it. Just a one-liner to get to this page–

The New Path of Legal Murkiness Surrounding Mistake Fares

Thus we are left wading through a murky pond of uncertainty concerning how the DOT will handle future (and inevitable) mistake fares. The DOT used what I call result-oriented jurisprudence, determining how it wanted to rule from the outset then contorting the law to make its pre-conceived decision work. This should not be celebrated, even by the United legal team members who must be patting themselves on the back tonight (for it could work against them next time).

The problem I see is that the DOT is rewarding sloppiness. Consumers will have to answer to their own conscience (and perhaps a fraud claim by United Airlines) for manipulating websites and billing addresses to produce cheaper prices, but ultimately this was pure sloppiness on the part of United (via its contractors) and sometimes the only way we improve is through painful failures and being forced, because of the severity of the pain, to be more scrupulous in conducting our work and supervising those who work for us.

We see a dangerous precedent in that the DOT pulled out totally new criterion from thin air for judging the validity of an airline ticket sold to U.S. consumers, touching U.S. soil, that was paid for and fully ticketed. There can be no certainty that the DOT will help consumers deal with any future unilateral airline rescission because the nebulous line between what is and is not a mistake fare now appears at the capricious whim of the DOT.

The DOT has made no secret of its frustration that travelers have used §399.88(a) to attempt to force airlines to honor “erroneous” fares, issuing a May 2014 Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) that included the following–

Finally, the Department is also contemplating revising the post-purchase price provision to better address the issue of “mistaken fares.” As explained above, section 399.88 essentially bans sellers of air transportation from increasing the price of an airline ticket to a consumer who has purchased and paid for the ticket in full. As a result, the Department’s Enforcement Office explained in a guidance document that, under section 399.88, “if a consumer purchases a fare and that consumer receives confirmation (such as a confirmation email and/or the purchase appears on their credit card statement or online account summary) of their purchase, then the seller of air transportation cannot increase the price of that air transportation to that consumer, even when the fare is a ‘mistake.’” Since then, the Enforcement Office has investigated a number of incidents where passengers complained that airlines or ticket agents would not honor tickets that had been paid for in full because the sellers of the air transportation erroneously let them book flights for less than the actual value. The Enforcement Office has become concerned that increasingly mistaken fares are getting posted on frequent-flyer community blogs and travel- deal sites, and individuals are purchasing these tickets in bad faith and not on the mistaken belief that a good deal is now available. We solicit comment on how best to address the problem of individual bad actors while still ensuring that airlines and other sellers of air transportation are required to honor mistaken fares that were reasonably relied upon by consumers.

My comment to the DOT is that you had it right the first time. As regrettable as this exploitation of airline mistakes may be, the alternative of weighing each error on case-by-case basis is even worse. A bright line rule is the best solution.

This NPRM is almost a year old and the fact that there has been no change in the law indeed suggests that there is no better solution that can be captured in words. I can think of one — which is also fraught with downsides — but giving airlines 24 hours to cancel as well, provided the ticket is booked more than seven days in advance, would be a much better compromise than abrogating a bright-line rule in favor of leaving in the hands of a DOT case officer the determination of whether or not a fare is a mistake.

For those who lost out on this fare, my advice is to throw in the towel and lobby the DOT to be unwavering in its future enforcement of post-purchase price increases. There is always court, but United has a much stronger legal argument under traditional contract law principles than under §399.88(a) and since the DOT has the statutory authority to promulgate its regulations, you will be left with cases like Lucy v. Zehmer as the basis of your legal defense. Good luck.

Coming Soon: A Devil’s Advocate View

Thanks for this post!

Me not being a lawyer, can you please explain what the big deal is with changing your billing address to Denmark on a Website? Theoretically had I walked into a United ticketing office at CPH airport, I would have been offered the same price, I assume, and could have paid cash without giving a billing address – even if I was a tourist visiting Denmark.

From the company’s point of view, what is the billing address even used as and why can it be used against me if I enter a fantasy address where I am not residing at? Even if I was living in the U.S., am I only allowed to us where I am officially residing at? the billing address of my credit card?

I just don’t get the fuss why submitting a Danish billing address is wrong?

Great analysis, thanks.

I’m actually Danish, paid my tickets with my Danish credit card, and had as such hoped that DOT would at least address my situation in their ruling.

Instead they claim precedence in “the Office’s treatment of fare advertisements and disclosure of baggage fees” to not address my complaint. Do you have insight into the actual cases behind this precedence, and it’s relevance to this case ?

Anthony Foxx is curently traveling all across America to do what bureaucrats do best: nothing, with a side of bs speeches and photo-ops. The DOT Twitter feed is an all out self glossing picture parade of him. All this travels and pictures and DOT material with talking points such as ‘millenials will be yada yada per cent of population until yada yada’ and ‘ten per cent of Americans take home half ‘OUR’ (bureaucrats actually believe the sum of of individual incomes are actually theirs to dispense to political clients and prospect voters) income’, tells me the guy who used to have his wife employed along the gravy train is soon to resume his political career. National stage now. Anyway, I’m glad he apparently secured corporate sponsorship for his ensuing venturing. And considering he badges the get out of jail free from scrunity big D beside his name, he’s certainly going to pull this perfectly.

Great article, I salude you.

That is some fairly sloppy reasoning – thanks for providing an explication.

If DOT weren’t interested in eroding § 399.88, it seems like they should have made United honor the fare. United’s recourse should be with the vendor who messed up, not with the customers. The contract should have included some definition of who is financially responsible for an incorrect exchange rate.

I mean, imagine if the error were much smaller and occurred over months. United sets a price on a route expecting a given return and instead they’re getting 95% of the expected return. That kind of error is costing United money invisibly, and it’s the vendor’s fault.

Or try the same thing in the opposite direction. United intends to fare match other airlines on a route, but due to the mistake the Danes see a price that’s USD50 or USD100 higher than the competition. That’s lost business to United. The vendor should still be culpable.

Anyway, that’s just one non-lawyer’s 2 øre..

It sounds like a bitter frequent flyer complaining for not getting his petty advantage. It is obviously an action of bad faith and you know it. Stop playing word games on whether United.com is facing US or Danish market. It’s all about people not in Denmark or without a Danish credit card manipulating their billing addresses to get the cheap fare.