Now to a different story concerning Maui. A final National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report on a near-crash involving a United Airlines 777 provides more chilling details about what exactly transpired off the coast of Maui.

Final Report Released On How United Airlines 777 Nearly Crashed Into Pacific Ocean Off Maui Coast

In February, I wrote about the chilling incident that occurred on UA1722 from Maui (OGG) to San Francisco (SFO) on December 18, 2022 utilizing a Boeing 777-200 aircraft.

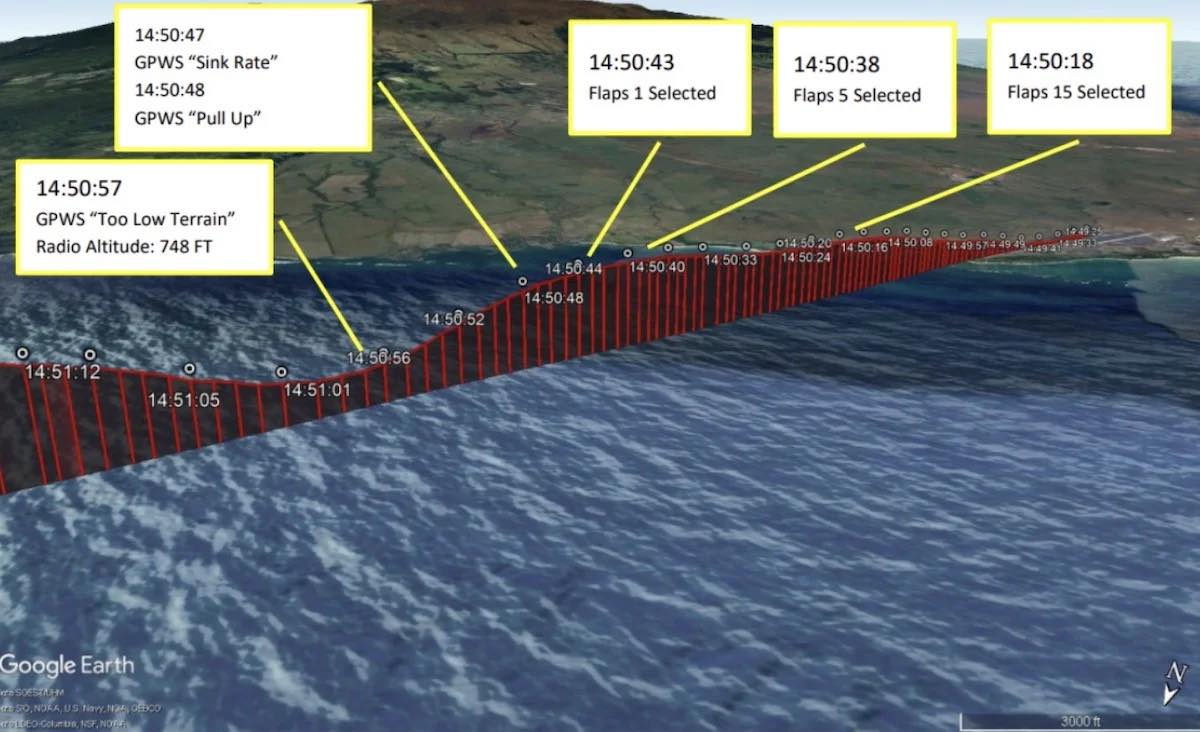

After departing Kahului Airport, the aircraft reached 2,100 feet before beginning a steep descent at a rate of 8,600 feet per minute. The aircraft recovered, but not before it dropped to only 748 feet over the Pacific Ocean. In other words, the aircraft and everyone onboard was seconds from disaster.

The flight continues to San Francisco without further incident. A passenger onboard told View From The Wing:

“My husband and I were on this flight sitting in the back of the aircraft. It happened soon after takeoff when we were all seated with seatbelts on. The plane dipped down and then up like a quick fall and recovery. While several people screamed, no one was injured and it was over quickly. We did not realize how close the plane got to the ocean. The rest of the flight was uneventful, so while it was scary, it ended up being a blip in the flight- though a memorable one.”

Now the NTSB has investigated and published its final report. The conclusions are not comforting.

“The flight crew’s failure to manage the airplane’s vertical flightpath, airspeed, and pitch attitude following a miscommunication about the captain’s desired flap setting during the initial climb.”

Here are key details from the final report (.pdf):

- The captain (who was the pilot flying) reported that he and the first officer had initially planned for a flaps-20 takeoff (flap setting of 20°) with a reduced-thrust setting, based on performance calculations

- However, during taxi, the ground controller advised them that low-level windshear advisories were in effect

- Based on this information, the captain chose a flaps-20 maximum thrust takeoff instead

- He hand-flew the takeoff, with the auto throttles engaged

- During the takeoff, the rotation and initial climb were normal; however, as the airplane continued to climb, the flight crew noted airspeed fluctuations as the airplane encountered turbulence

- When the airplane reached the acceleration altitude, the captain reduced the pitch attitude slightly and called for the flap setting to be reduced to flaps 5 (five degrees)

- According to the first officer, he thought that he heard the captain announce flaps 15, which the first officer selected before contacting the departure controller and discussing the weather condition

- The captain noticed that the maximum operating speed indicator moved to a lower value than expected, and the airspeed began to accelerate rapidly

- The captain reduced the engine thrust manually, overriding the auto throttle servos, to avoid a flap overspeed and began to diagnose the flap condition

- He noticed that the flap indicator was showing 15°, and he again called for flaps 5, and he confirmed that the first officer moved the flap handle to the 5° position

- The first officer stated that he “knew the captain was having difficulty with airspeed control”, and he queried the captain about it as he considered if his own (right side) instrumentation may have been in error

- He did not receive an immediate response from the captain

- Both pilots recalled that, about this time, the airplane’s pitch attitude was decreasing, and the airspeed was increasing

- The first officer recalled that that the captain asked for flaps 1 soon after he had called for flaps 5, and when the first officer set the flaps to 1°, he then noticed the airspeed had increased further, and the control column moved forward

- Both pilots recalled hearing the initial warnings from the ground proximity warning system (GPWS), and the first officer recalled announcing “pull up pull up” along with those initial GPWS warnings

- The captain then pulled aft on the control column, initially reduced power to reduce airspeed, and then applied full power to “begin the full CFIT [controlled flight into terrain] recovery”

- The first officer recalled that, as the captain was performing the recovery, the GPWS alerted again as the descent began to reverse trend; data showed this occurred about 748 ft above the water

- After noting a positive rate of climb, the captain lowered the nose to resume a normal profile, ensured that the flaps and speed brakes were fully retracted, and engaged the autopilot

- The remainder of the flight was uneventful

- As a result of the event, United Airlines modified one of its operations training modules to address this occurrence and issued an awareness campaign about flight path management at their training center

Credit must be given to Jon Ostrower of The Air Current, who discovered this anomaly based on public data and wrote about it: this was not self-reported by United until the incident was exposed by him and United did not preserve flight data from the aircraft.

CONCLUSION

Pilot communication during the critical takeoff period nearly led to the loss of a 777-200 filled with passengers. This is no exaggeration. I am very thankful the pilots recovered with just seconds to spare and hope this near-miss will be used as a teaching moment for all pilots.

What are your thoughts on the incident?

I’m not a pilot but I would assume you need to use the Auto pilot with the Auto throttle . Not hand fly it.

I would have increased the pitch altitude and set the flaps -3 degrees. Then I would have lifted the nose and yelled at my co-captain.

Btw, I’m not a pilot either.

Careful. There is an old adage in flying: If you want to go up, pull back on the stick, if you want to go down pull back further. At a critical airspeed the latter activity may result in a stall, then you’re in real trouble especially at very low altitudes.

So self reporting is optional for airlines? That doesn’t sound like a good idea.

Its terrible this wasn’t reported quickly; they didn’t want this to have any effect on the heavy Holiday season flying volume; wanted to keep it quiet to after the high season of flying.

No, they wanted to not report it at all. This “safety is our top priority line” is a PR slogan.

Does United want planes creating? No, it doesn’t.

Wooo it cover-up Koska is whenever it can, to avoid unearthed investigations and scrutiny, including erasing key information – evidently yes.

Notice that the timeline provided has a few gaps and inconsistencies (did the co-pilot hear 5, or 0?).

We have no voice recordings, and have no way to know the crew are telling the truth. Certainly not the whole truth, if it’s too embarrassing or negligent on their part,

The fact the these recordings are not streamed to the ground in real time is inexcusable, and is a testament to the destructive power unions exercise, even in matters of flight safety.

United did not report the incident to the NTSB because it was not, by definition, an NTSB-reportable incident. There are defined criteria for doing so.

The pilots self reported the anomaly through the customary channels, the company reviewed it, and made changes to its training curriculum as a result of issues identified. Those changes were independent of any media attention. This is an operator-level issue that was handled by the operator.

The public reporting on the event does not make the system any safer and leads to wild speculation (like here) that does nothing productive.

A widebody commercial passenger jet comes within 750ft of catastrophically crashing, and this is not reported because it doesn’t meet certain criteria. Your response is to defend this?

In my field, which is far from perfect, we have a “near-miss” reporting pathway to allow folks to report events that can teach the profession about potentially dangerous events.

It’s not reported to the NTSB, but it is reported to the FAA. There’s some nuance missing here, both the airline and the government regulator have done some level of investigation, it’s not like the airline pretended it didnt happen. They just didn’t report it to the body who’s own criteria does not expect a report.

Thank you for this clarification– makes much more sense.

I think this incident shows why it is so important to have at least 3000 hours experience before flying a jet aircraft.

(Yes, I know the above is nonsensical, but so is the arbitrary 1500 hour rule!).

Was there engine failure⚠️ or why did the plane dive. Do you know ?

Matt, my thoughts:

I re-read the above report 5 times and apparently it can be summed up as due to a miscommunication between the Captain and First Officer to reduce flaps to 5 instead of 15. This was sufficient to cause a loss of altitude for the aircraft until it was corrected. According to the figures provided, I calculate this all happened in a space of about 10 seconds. The observations from the incident apparently are that a mistake happened and the crew was professional and efficient at handling the issue quickly and how critical it is that a 10 degree difference in flap settings could bring down an aircraft at the two most critical moments in a flight (takeoff and landing.)

This is a human issue, not technical. I think the 1st officer knew it would be critical to lower flaps after takeoff due to his flight hours but didn’t openly question what he thought was the captain’s instruction to reduce them only from 20 to 15.

So the IMPORTANT takeaway from this may be that the first officer was afraid to question the captain’s authority by saying (literally) “Captain, did I hear you correctly? Did you say flaps at 15?” and the Captain would have said “No, you didn’t. I said flaps at 5” and that would have been that.

Three of the greatest disasters of engineering history include the 737 Max, Chernobyl and the Space Shuttle Challenger where engineers were afraid to challenge authority and speak up against risky practices. In the case of the Challenger specifically, Thiokol executives covered up the risks of the O rings and a whistleblower was punished. IMO, executives should have been sent to a non country-club Federal prison. Same thing with the Boeing executives particularly CEO Dennis Muilenburg who tried to downplay the issue as a “software patch.” The Thiokol engineer whistleblower faced termination and it took a conscientious senator to go to bat for him.

“For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for Nature cannot be fooled.” — Richard Feynman, Appendix F

Don’t forget the fourth greatest disaster (and directly related to airlines) was The KLM – Pan AM collision at TFE. Both the KLM FO and FE were afraid to question the very senior Captain/Flight instructor when they knew they were only cleared for departure, not for take off, and they knew they didn’t get confirmation that the Pan Am 747 had cleared the runway yet.

PolishKnight has a good point, but it was something we did routinely in the command/response checklist procedure we used in Military Airlift Command (MAC) and is still used in Air Mobility Command (AMC) especially during take-off/climb-out and approach procedures to ensure that the gear and flaps were in the commanded position. It’s why you have a co-pilot. This was sloppy crew coordination, potentially worse, it was a sense of complacency that could infiltrate other flight deck activities.

The really scary part for me was the Captain’s initial intention to take-off at less than MAX POWER. That choice must have been a company directed requirement for noise abatement or fuel savings. In either case, bad decision until the possibility of low level turbulence was transmitted and the T/O power setting was changed

My concern isn’t that the flaps were in the “commanded position” but rather that the first officer may not have felt comfortable to question what he should have known was a bad request.

Regarding not taking off at max power: I find that amusing similar to the Spinal Tap “volume at 11” in that if a safe takeoff power is at max, does that mean the aircraft has a lower margin of safe power for takeoff? I can see it would be “safer”, but it shouldn’t be a big deal particularly if it’s not at maximum takeoff load weight. Tragically, the LOT Polish Airlines flights 007 and 5055 crashed precisely because they took off at full power and the engines were unsafe at that power level (which meant a crash was going to happen sooner or later.) I resist running engines at full power in order to get better reliability out of them.

Damn you DEI hires who are the result of Woke United lowering its standards!

(Oh wait – probably two middle aged white guys in this case? Usual suspects stay quiet…)

They let you on the internet in prison? Isn’t that how the whole thing started?

Why would changing the flaps from 20 to a higher setting (15) than called for (5) cause a loss of altitude? I thought flaps increased lift of the wings for a given airspeed.

The pilots lost their situational awareness on the pitch attitude. At flaps 15, the maximum speed you can travel is lower than at flaps 5 due to forces on the flaps. The maximum speed is marked on the airspeed indicator. The captain noticed the mark was at a lower value than he expected so he reduced power to not exceed the airspeed limit. As both crew members focused on the flaps, it seems neither noticed that pitch was decreasing and causing airspeed to rise. That’s why the NTSB wrote that it was a failure to manage pitch, airspeed, and vertical flight path. This had some similarities to the Eastern Everglades crash.

Flaps do increase lift for a given airspeed, but you can still pitch the airplane nose down and descend if you don’t pay attention.

The reduction in engine power can also cause the nose to drop on an airplane with wing mounted engines if the trim is not adjusted accordingly.

I believe your explanation of what happened is the best I’ve read, which makes it all the scarier. It sounds like if it were not for the GPWS this airplane would have crashed.