Airlines are happy to award more miles to customers who spend more money. But they sometimes forget that releasing premium award seats (business and first class) is better for the balance sheet too.

If you are considering booking travel or signing up for a new credit card please click here. Both support LiveAndLetsFly.com.

If you haven’t followed us on Facebook or Instagram, add us today.

Miles Are Liabilities

Frequent Flyer award miles and points are liabilities for airline businesses as they represent future material costs. As mileage sales and mileage accrual are big business for the carriers, and many are public companies, the details of just what those costs represent are easy to find.

Using a base cost of about .14¢/mile (that’s not to be confused with 1.4¢/mile average redemption value for the traveller, nor 3.0¢/mile for which they often sell) American Airlines had a liability of approximately $2.45bn in 2015. Customer Think has a great explanation of this murky space of the airline business, and while dated, the information remains true today though the figures have changed.

American’s loyalty liability grew to $3.267bn according to the Q2 2019 results.

American Airlines Should Release More Space

American Airlines has the most debt of any peer airline, $18bn at the end of the last quarter, of which frequent flyer miles are not a true liability. Their debt is largely the result of fleet renewal, something the carrier has been more ambitious about than peers, specifically than Delta.

But American has made the road tougher for themselves. Fleet inconsistencies drive up costs, along with the failure to combine labor groups or even produce a contract. Verbose statements have not helped the cause and just a few weeks ago, American’s stock (AAL) hit a 52-week low. I finally decided to pick up some shares, not because I think it’s hit rock bottom, but because it can only get better from here.

American has taken aim at their loyalty (proverbial foot) and fired. They have made status harder, tied mileage accrual to revenue just like the others. But what’s worse, American Airlines then also increased the price of their premium award (business and first-class) and released less space.

Management’s (apparent) thought process is that if awards are less likely available and fewer upgrades are given, passengers will be more likely to buy the tickets. Except that’s not been the case. From 2015-2018 American flew between 144-148MM passengers with a minimal upward trend. However, profits are down, stock performance has disappointed, and yet American’s mileage liability is up 33% in just three years. That weighs on their financial performance.

American could immediately shed financial liability and shore up their balance sheet with near immediate effect by releasing premium cabins at saver level prices to fill otherwise empty seats. Passengers aren’t buying up, and American isn’t outpacing general aviation market growth (in fact they are underperforming.)

United and Delta Should Lower Prices Too

United and Delta’s award prices are prohibitively high, evidence of this is everywhere. United has some of the most expensive business and first-class redemption prices in the business. Delta is no better, in fact, it’s hard to say how much more expensive Delta premium cabin long haul redemptions cost because they no longer hold an award chart.

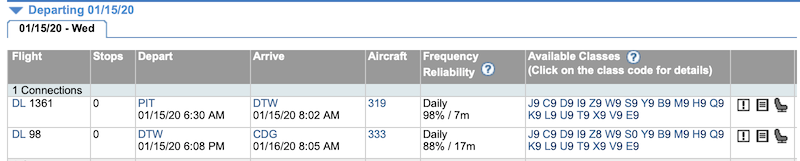

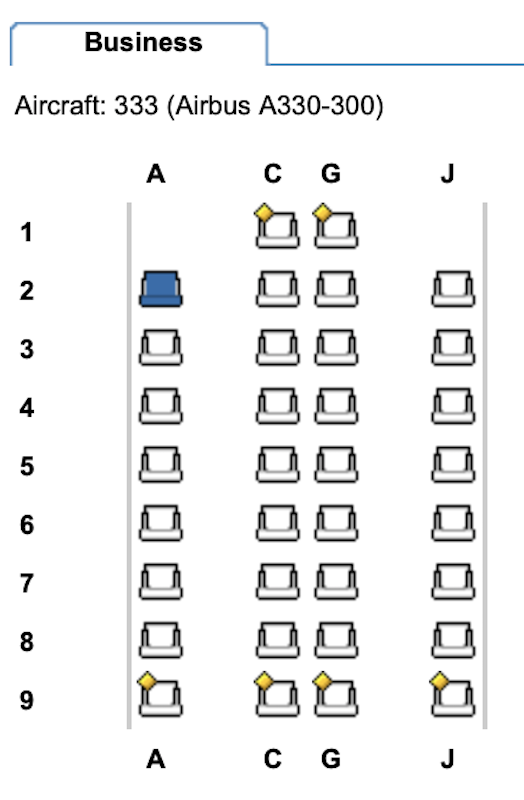

I’ll give two small examples. First, Delta One service on what should be the absolute lowest possibly load factor for the route: Pittsburgh-Detroit-Paris, January 15-22nd. Expert Flyer shows they have the maximum level of seats available for sale, it’s a Wednesday flight and the flight is currently four months out. Availability does not get more open than this. Delta’s standard price is clearly 160,000 roundtrip with $262 in taxes and fees.

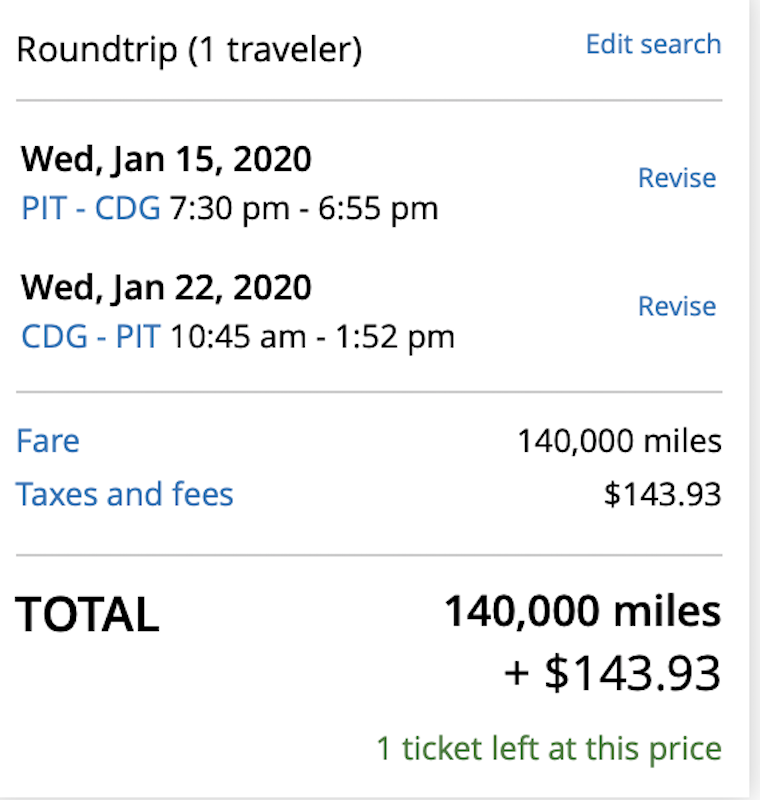

United has two stop service (connecting leg from Pittsburgh to Chicago is in coach) from 140,000 miles and $144 roundtrip.

American is the cheapest in the market at 115,000 points and $131 roundtrip in taxes. If you were ever wondering just how wide open those dates usually are, American is showing roundtrip availability in business at saver level 0n their own metal – if the dates were better that would be known as a unicorn.

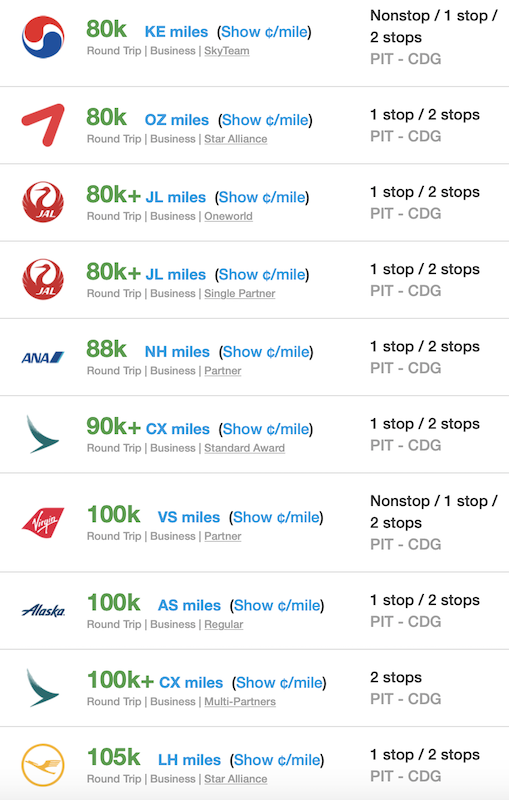

To underscore the point of just how much better everyone else’s award charts are, here are the cheapest for the same routes (fly SkyTeam using Korean for 80,000 miles, Star Alliance on Asiana, Japan Airlines on oneworld.) Asia is worse but, due to its geographic expanse, is a little harder to accurately display on a chart.

The real issue facing Delta and United specifically is in the competition they face with their own credit card issuers. Despite Delta securing an excellent deal with AMEX earlier in the year, flexible bank currencies like Chase Ultimate Rewards and AMEX Membership Rewards compete with their airline and hotel points partners.

An easy look at competing charts will show that US carriers award charts are prohibitive nearly carte blanche to all foreign carriers, especially for specific use cases. Singapore charges far less for mainland US to Hawaii roundtrips in business class on the same United aircraft that United Mileage Plus would book. If you have Ultimate Rewards points why would a Sapphire cardholder transfer their Ultimate Rewards points to United over Singapore?

Airlines Can Strengthen Balance Sheet, Keep Premium Customers

Delta is doing a great job of releasing coach awards for long haul flights in sales. They are, unfortunately, for limited markets and limited periods of time. However, Delta, United and American could all clear their balance sheets and improve their financial position by reducing mileage liabilities instead of making miles harder to use.

Last week I discussed how the majority of customers have the potential to benefit from some of the improved variability and lower redemption levels, but premium cabins have two different effects that coach awards do not. Premium award cost more which would help to clear more liability faster. Second, experiences in business class may engender more loyalty and activity from the traveller to repeat the effect. If a local coffee shop on your way to work had a punch card where the 10th coffee was free, you might make it part of your habit in the morning. But if there was an equally convenient coffee shop next to it that offered a free coffee after five visits – and they sold the same exact brand of coffee – you would likely switch your loyalty.

By lowering the barrier on the very best products the airlines have to offer, it can help to introduce a new market and fill seats and reduce liability at the same time. Premium customers want premium award seats for travel with their family. By releasing more for these customers, airlines further entrench the best customers with the brand.

What do you think? Are airlines removing enough miles from their balance sheet? Are premium seats a good way to do that?

Nicely said. Given the presumption (I’m not sure, but work with me here) that the airline CEOs are not idiots, why on Earth would they not see the numbers as you do and implement these changes?

This. Might be the best damn analysis and article written in years on miles.

In the case of American they honestly don’t care. I swear it’s an insider system developed by their employees to assure the most possible non-rev seats in First and business so that they can all jump on Intl flights at a whim in these premium cabins. Just fly any F cabin to London or Sao Paulo on the 777-300’s. There’s maybe one legit passenger and the rest are all non-revs.

Wall Street does not care about FF liabilities. Therefore it does not affect stock prices or executive comp. Period. End of story.

As somebody who works in and with frequent flyer programs, I unfortunately have to say that this post contains some fundamental misunderstandings about how FFP liability works and how more (premium cabin or otherwise) redemptions affect an airline’s financials.

It’s too complicated to elaborate here but the key components are

– unlike aircraft leasing debt, FFP liability is fully funded (i.e. money sits in a pot waiting to be used)

– making redemptions less expensive increases the cost per mile redeemed, and thus the amount of money that needs to be booked into the liability for outstanding miles. So less expensive redemptions means higher liability.

– making redemptions more available reduces breakage (points going unused), which means liability for outstanding points goes up.

RE: breakage – how do you explain Delta and United getting rid of expiration dates? They just automatically increased their outstanding liability. Is this why they timed this along with getting rid of award charts so they can better manage the size of their funded pool of money?

Correct – it is no coincidence that the elimination of formal miles expiry goes hand in hand with the elimination of formal award charts.

DL and UA will replace the profit they got from breakage with personalized pricing (and mileage devaluation via price inflation). It’s a more engaging marketing message and gives you more management flexibility to control program profitability.

Could you also delve into why most airlines don’t just release all open seats to award redemptions at, say, 48 hours before the flight? How is it that empty seats are more profitable than someone spending miles? This has never made sense to me yet seems to be fairly normal.

Well, with dynamically priced “any seat” availability, many airlines do now allow FFP redemptions on all seats, at the mileage equivalent of the prevailing dollar price.

The rest is simple yield management: An airline tries to maximize profits on each flight. That sometimes means leaving some seats empty:

If you have 5 seats left on your Monday morning JFK-ORD flight 24h before departure, it is better to sell one to the businessman who absolutely needs to travel at $600 then to sell all five at $75 each just to fill the plane. Also, if there should be a second businesswoman showing up 2h before departure, you still have another seat to sell her at $800….